China-linked APT24 hackers have been using a previously undocumented malware called BadAudio in a three-year espionage campaign that recently switched to more sophisticated attack methods.

Since 2022, the malware has been delivered to victims through multiple methods that include spearphishing, supply-chain compromise, and watering hole attacks.

Campaign evolution

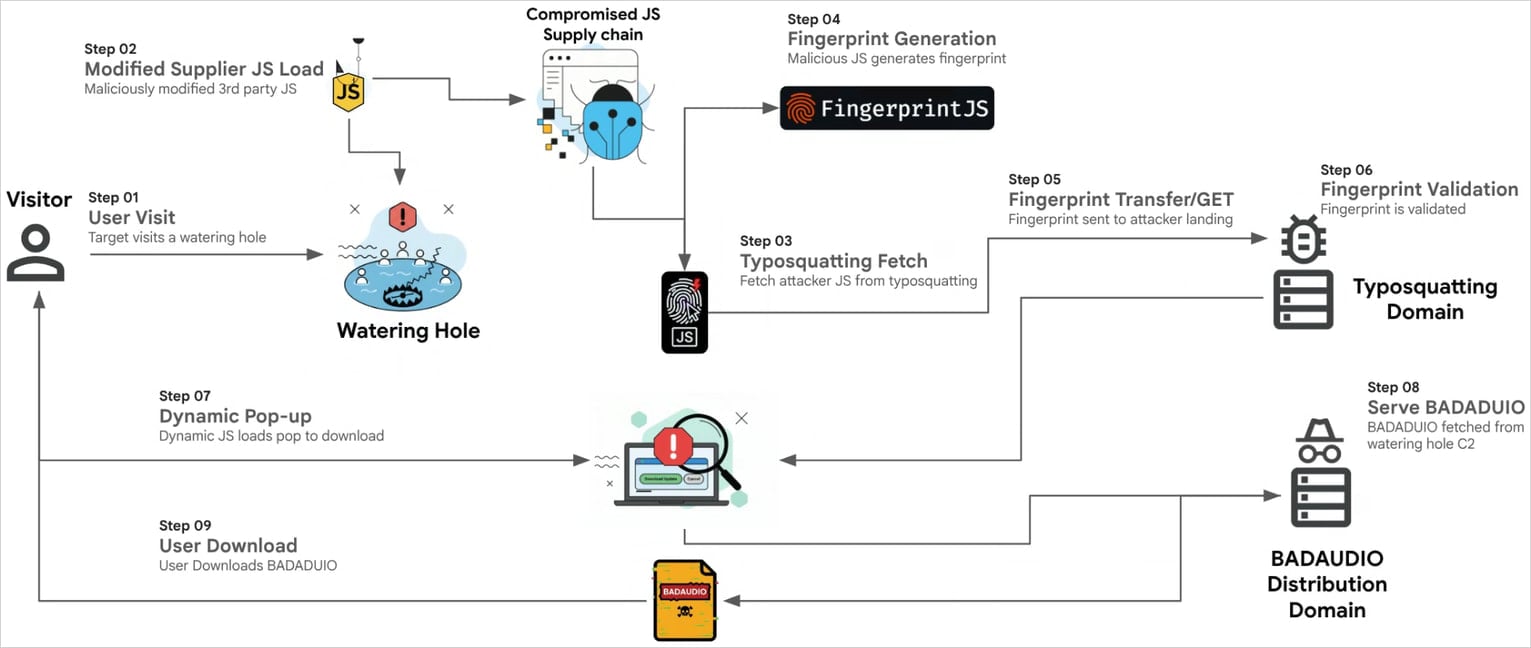

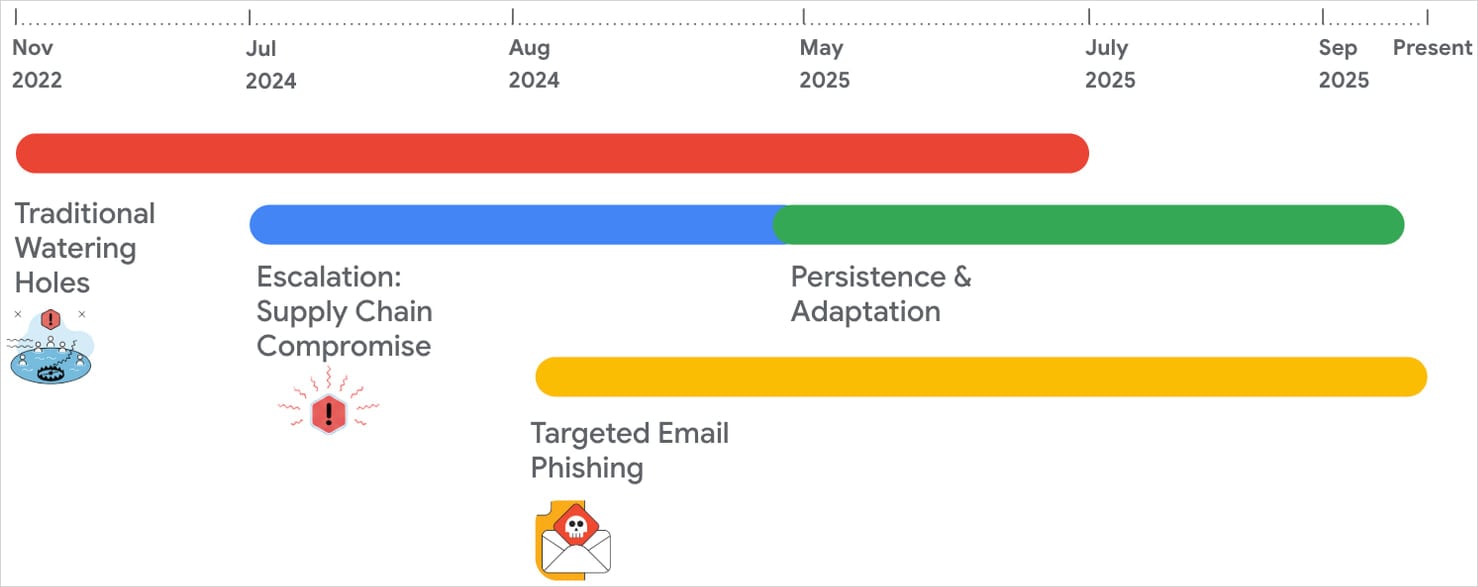

From November 2022 until at least September 2025, APT24 compromised more than 20 legitimate public websites from various domains to inject malicious JavaScript code that selected visitors of interest – the focus was exclusively on Windows systems.

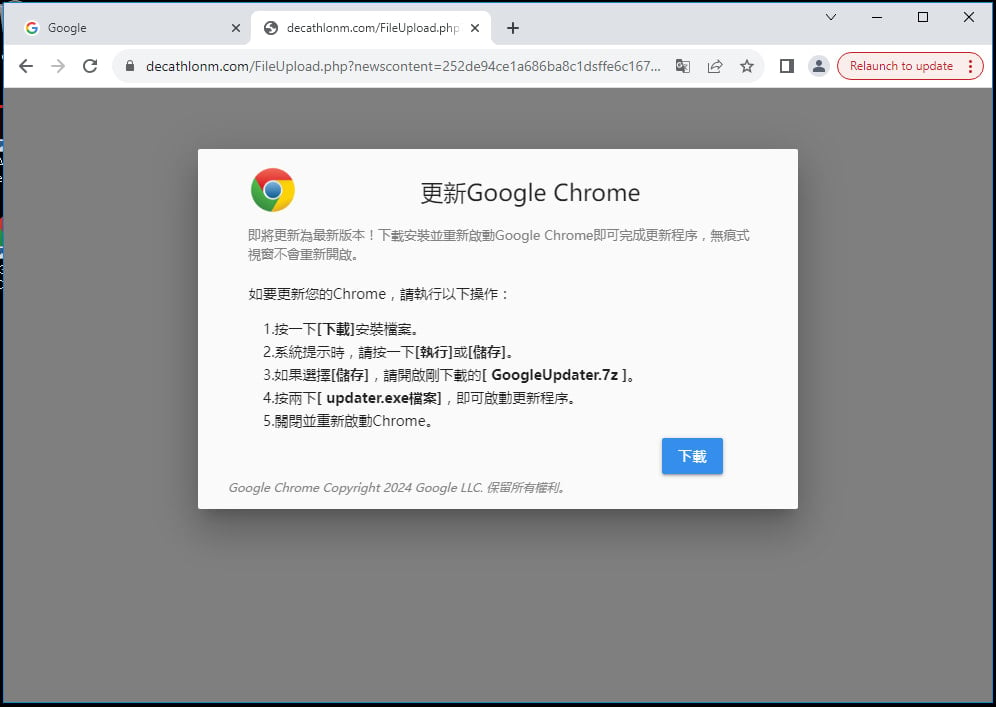

Researchers at Google Threat Intelligence Group (GTIG) say that the script fingerprinted visitors who qualified as targets and loaded a fake software update pop-up to lure them into downloading BadAudio.

Source: Google

Starting July 2024, APT24 compromised multiple times a digital marketing company in Taiwan that provides JavaScript libraries to client websites.

Through this tactic, the attackers injected malicious JavaScript into a widely used library that the firm distributed, and registered a domain name that impersonated a legitimate Content Delivery Network (CDN). This enabled the attacker to compromise more than 1,000 domains.

From late 2024 until July 2025, APT24 repeatedly compromised the same marketing firm by injecting malicious, obfuscated JavaScript into a modified JSON file, which was loaded by a separate JavaScript file from the same vendor.

Once executed, it fingerprinted each website visitor and sent a base64-encoded report to the attackers’ server, allowing them to decide if they would reply with the next-stage URL.

Source: Google

In parallel, starting from August 2024, APT24 launched spearphishing operations that delivered the BadAudio malware using as lures emails that impersonated animal rescue organizations.

In some variants of these attacks, APT24 used legitimate cloud services like Google Drive and OneDrive for malware distribution, instead of their own servers. However, Google says that many of the attempts were detected, and the messages ended up in the spam box.

In the observed cases, though, the emails included tracking pixels to confirm when recipients opened them.

Source: Google

BadAudio malware loader

According to GTIG’s analysis, the BadAudio malware is heavily obfuscated to evade detection and hinder analysis by security researchers.

It achieves execution through DLL search order hijacking, a technique that allows a malicious payload to be loaded by a legitimate application.

“The malware is engineered with control flow flattening—a sophisticated obfuscation technique that systematically dismantles a program’s natural, structured logic,” GTIG explains in a report today.

“This method replaces linear code with a series of disconnected blocks governed by a central ‘dispatcher’ and a state variable, forcing analysts to manually trace each execution path and significantly impeding both automated and manual reverse engineering efforts.”

Once BadAudio is executed on a target device, it collects basic system details (hostname, username, architecture), encrypts the info using a hard-coded AES key, and sends it to a hard-coded command-and-control (C2) address.

Next, it downloads an AES-encrypted payload from the C2, decrypts it, and executes it in memory for evasion using DLL sideloading.

In at least one case, Google researchers observed the deployment of the Cobalt Strike Beacon via BadAudio, a widely abused penetration-testing framework.

The researchers underline that they couldn’t confirm the presence of a Cobalt Strike Beacon in every instance they analyzed.

It should be noted that despite using BadAudio for three years, APT24’s tactics succeeded in keeping it largely undetected.

From the eight samples GTIG researchers provided in their report, only two are flagged as malicious by more than 25 antivirus engines on the VirusTotal scanning platform. The rest of the samples, with a creation date of December 7, 2022, are detected by up to five security solutions.

GTIG says that APT24’s evolution towards stealthier attacks is driven by the threat actor’s operational capabilities and its “capacity for persistent and adaptive espionage.”